Every sheet music, no matter how simple or complex, begins with the same building blocks: notes. They are the symbols that tell us what to play and how long to play it, forming the foundation of melodies and harmonies.

Learning to read and write notes on scores is one of the most essential skills for any musician or composer. With music notation, sound can be captured, shared, and performed by anyone, anywhere.

In this guide, we’ll break down everything you need to know about music notes: their names, how to read them on the staff, the different types of notes, and how accidentals shape pitch. By the end, you’ll have the tools to confidently start writing your own sheet music.

What Is a Musical Note?

At its core, a musical note is a symbol that represents sound. It tells us two essential things:

- Pitch – how high or low the sound is.

- Duration – how long the sound should last.

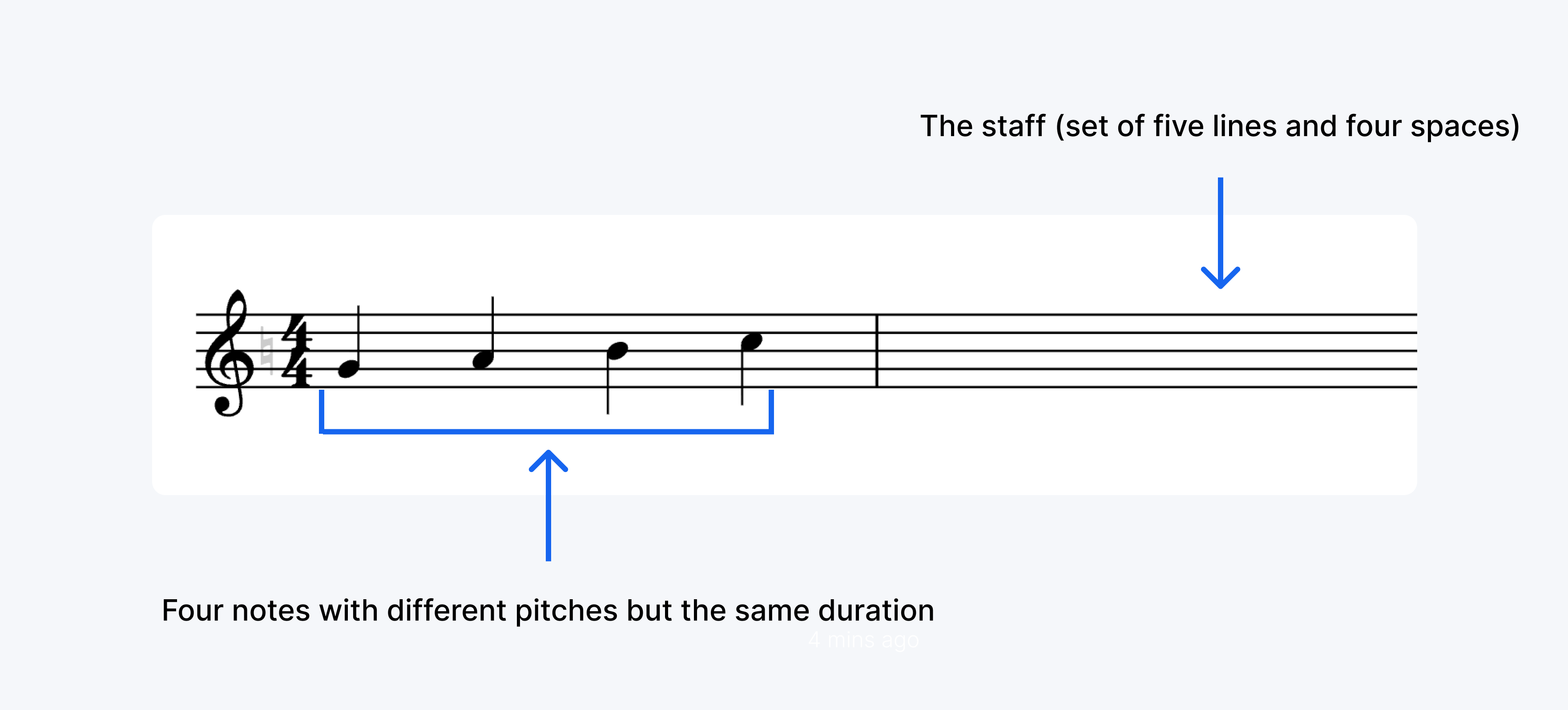

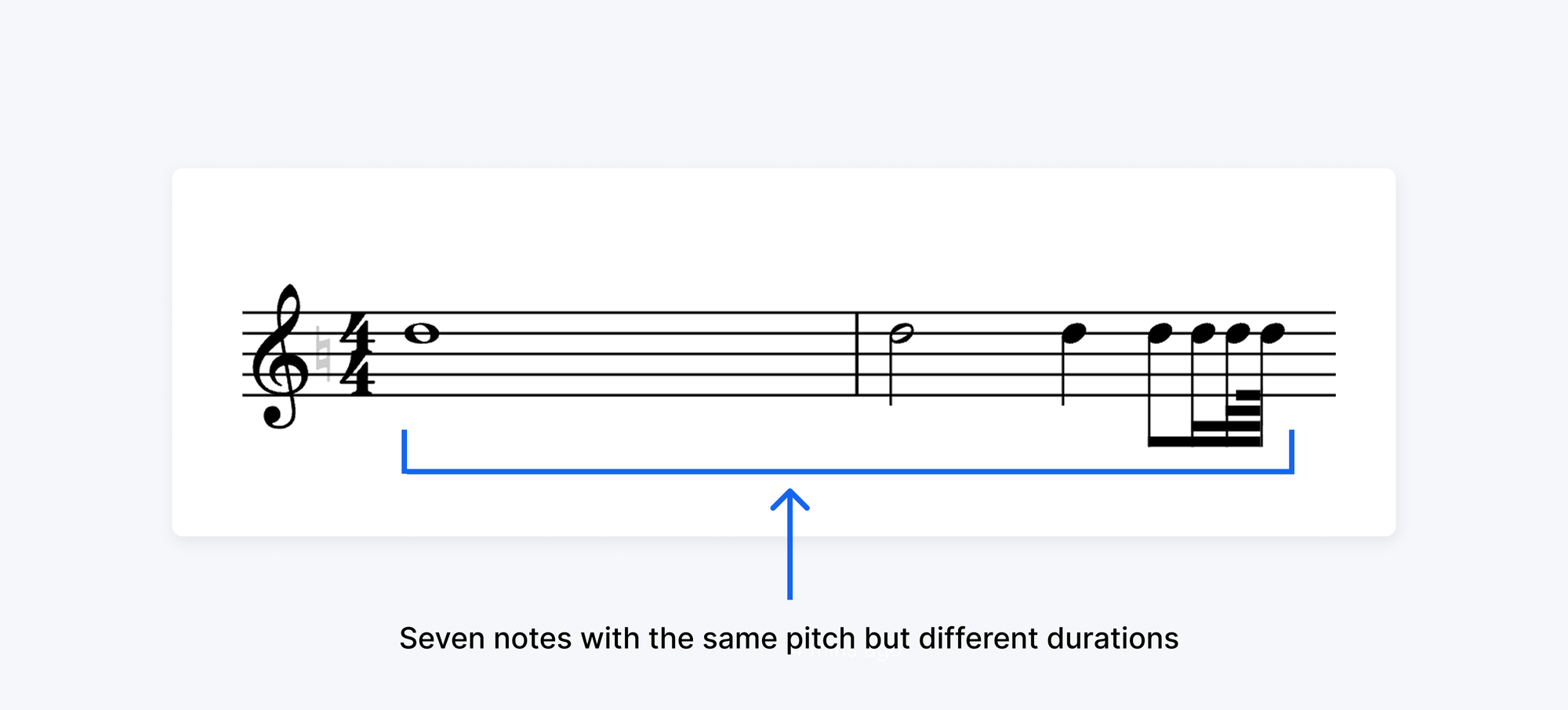

On a score, pitch is shown by the note’s placement on the staff (the set of five lines and four spaces), while duration is shown by the shape of the note—whether it’s open, filled in, has stems, beams, etc.

Sheet music examples showing four notes with different pitches but the same duration, and seven notes with the same pitch but different durations on a staff.

Think of notes as the alphabet of music. Just like letters combine into words and sentences, notes combine into rhythms, melodies, and harmonies. Without them, there would be no way to organize musical ideas or communicate them to performers.

Note Names by Pitch and the Staff

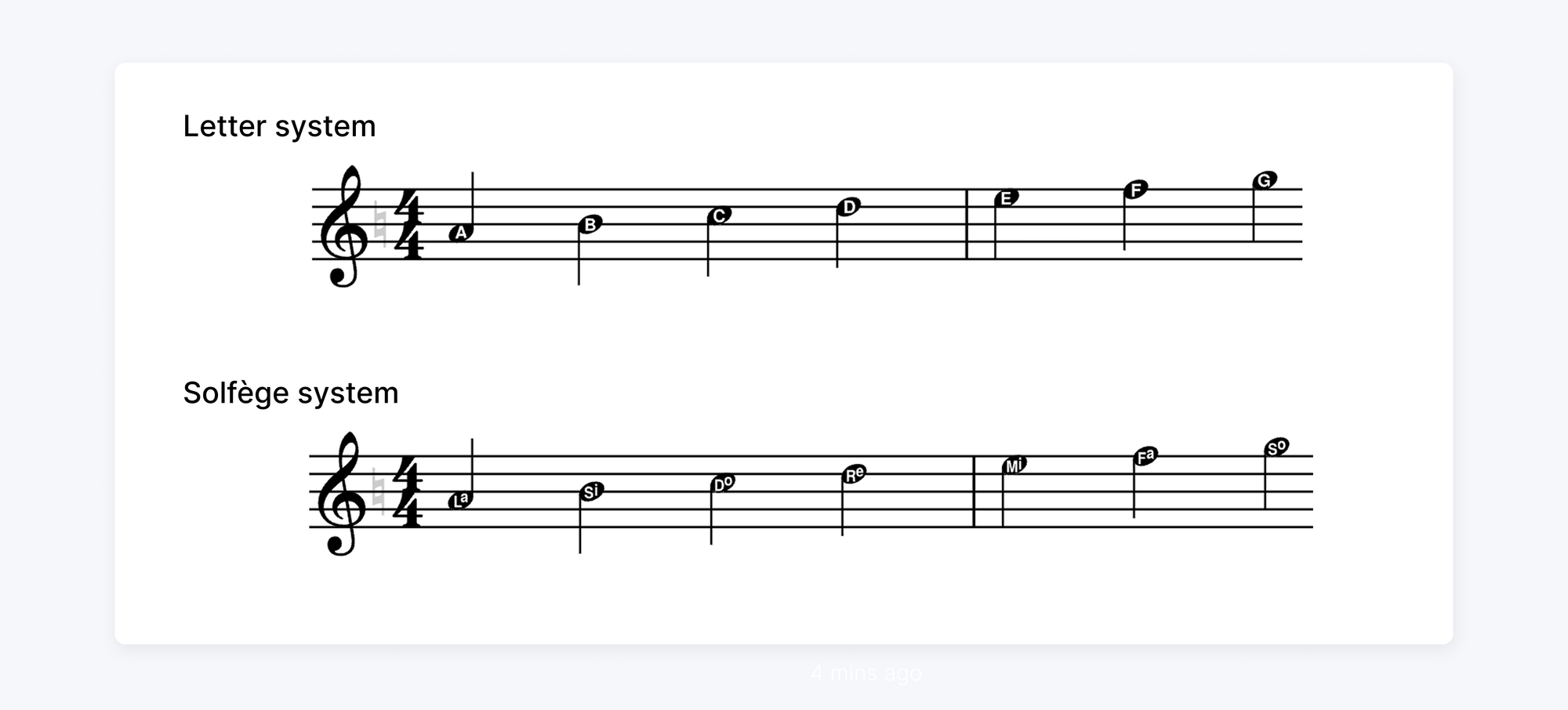

In Western music, everything starts with seven natural note names, which correspond to seven different pitches: A (La), B (Si), C (Do), D (Re), E (Mi), F (Fa), G (Sol).

You might notice there are two ways of naming the same notes:

- The letter system (A–G) is common in English-speaking countries and in most modern theory contexts.

- The solfège system (Do, Re, Mi, etc.) is widely used in Romance-language countries and in teaching to help singers and beginners hear pitch relationships.

Both systems describe the same notes, but the choice depends on the context. Letter names are standard in sheet music, theory, and analysis, while solfège is often used in ear training, vocal work, and classical teaching.

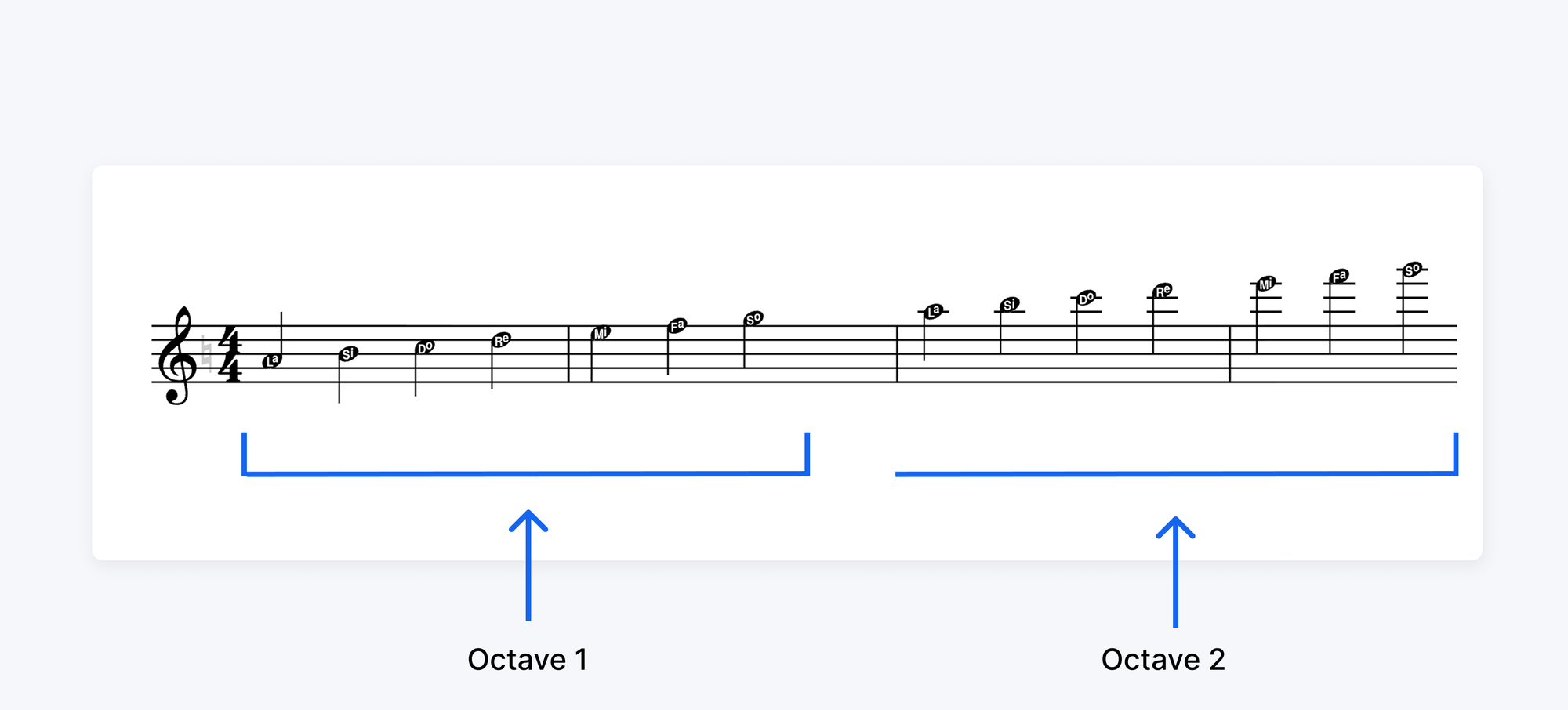

After G, the sequence starts over at higher or lower levels, called octaves. An octave is the distance between one note and the next of the same name, either higher or lower in pitch.

For example, the note G can be found in many ranges on the piano, but all Gs sound connected—each is either twice or half the frequency of another. That’s why they share the same name. Let's listen to the example:

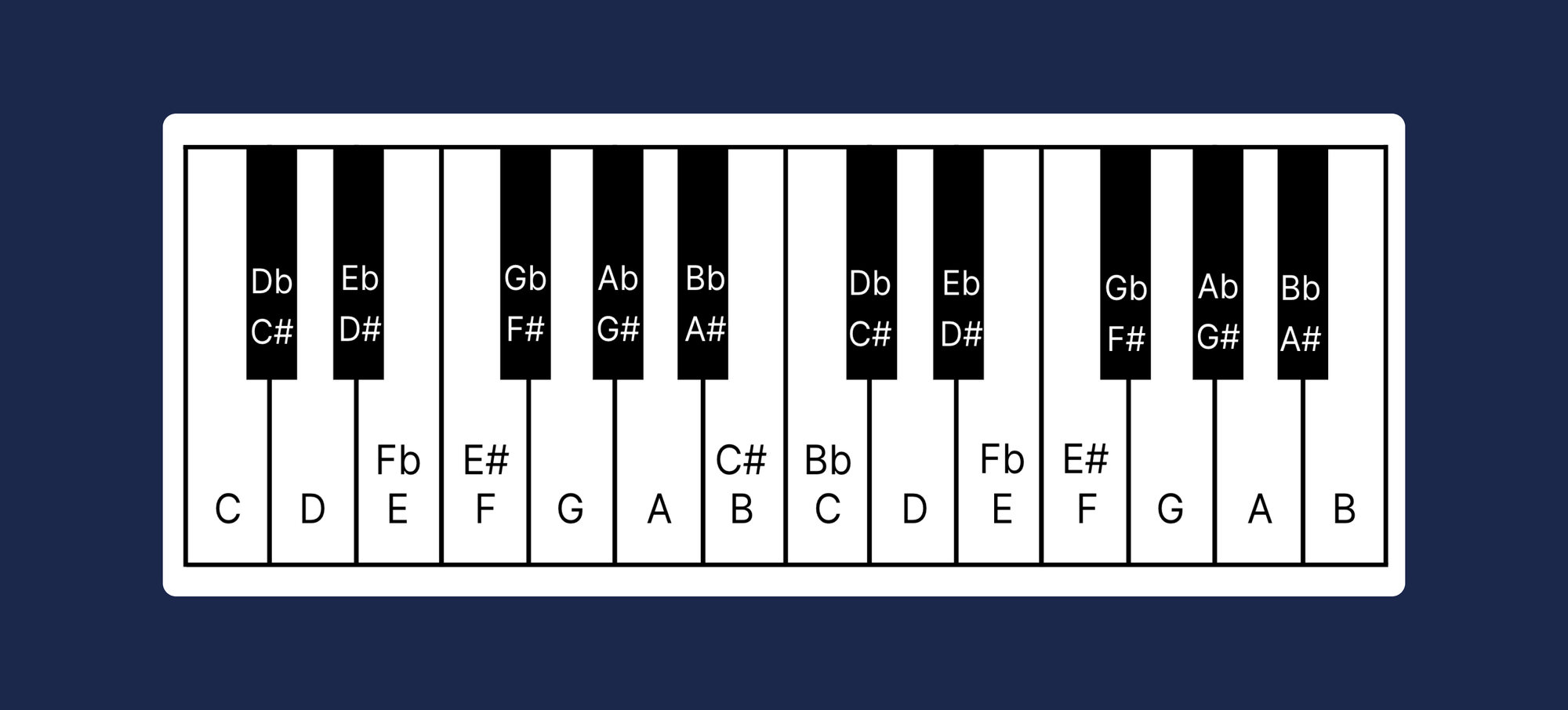

On a piano, the white keys represent the natural notes, while the black keys are their altered forms (sharps and flats—we’ll explain these in depth later). Together, they make up the full set of 12 distinct pitches used in Western notation, repeated across octaves:

A – A♯/B♭ – B – C – C♯/D♭ – D – D♯/E♭ – E – F – F♯/G♭ – G – G♯/A♭

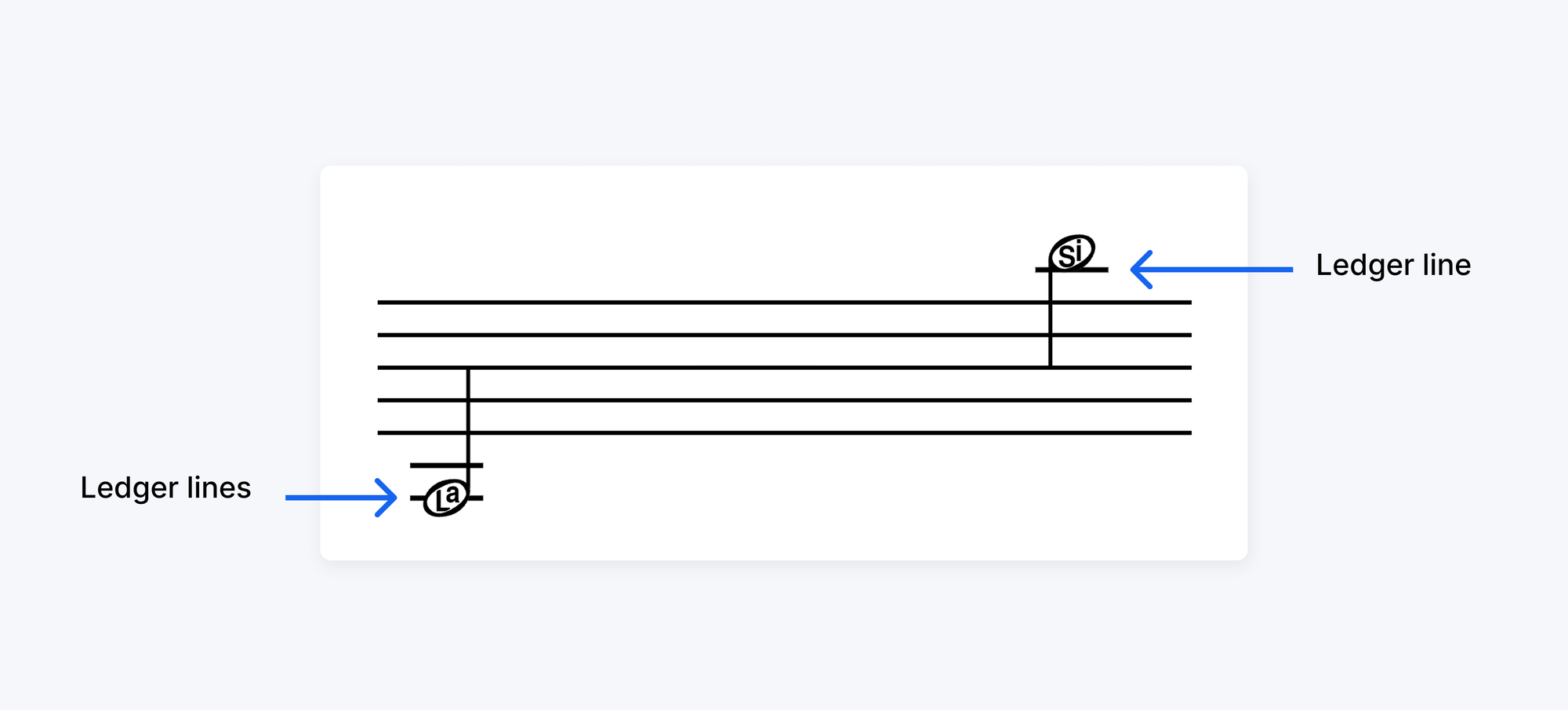

As mentioned above, music is written on a staff—a set of five lines and four spaces. Each line or space represents a specific pitch, and moving step by step (from a line to the next space, or from a space to the next line) follows the sequence of the musical alphabet (A to G). If a note extends higher or lower than the staff, we use short additional lines called ledger lines to show its position.

The clef

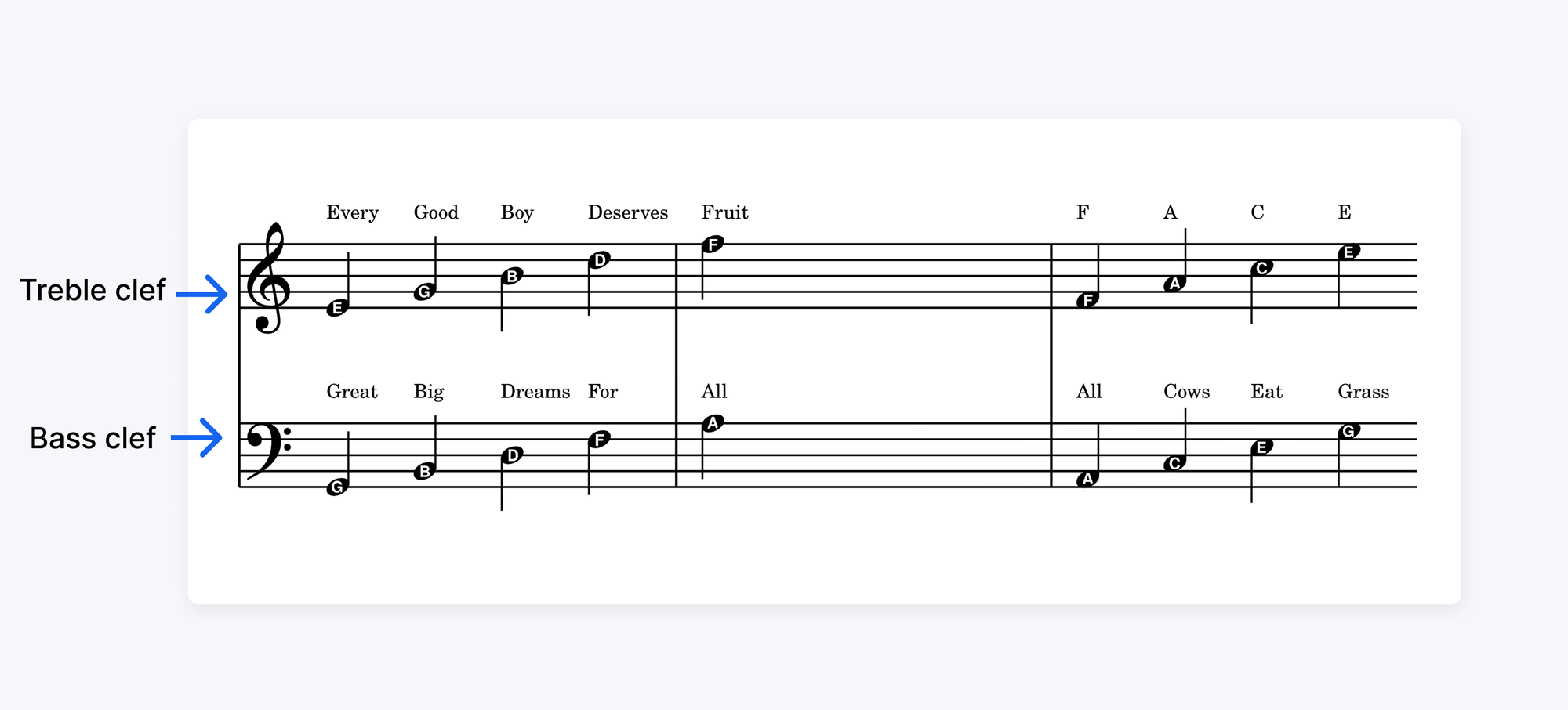

To know exactly which notes belong to those lines and spaces, we use clefs. A clef is a symbol placed at the beginning of the staff that anchors the pitches. There are several types of clefs, but for this article we’ll focus only on the treble and bass clefs. These are by far the most common and the best starting point for beginner composers.

- Treble clef (G clef): Its curl circles the line for G, just above Middle C. It’s used for higher-pitched instruments and the right hand of the piano.

- Lines (bottom to top): E – G – B – D – F → Every Good Boy Deserves Fruit

- Spaces: F – A – C – E → FACE

- Bass clef (F clef): Its two dots frame the line for F, just below Middle C. It’s used for lower-pitched instruments and the left hand of the piano.

- Lines: G – B – D – F – A → Good Big Dreams For All

- Spaces: A – C – E – G → All Cows Eat Grass

👉 Mnemonics like these are a handy way to memorize which notes belong to each line and space.

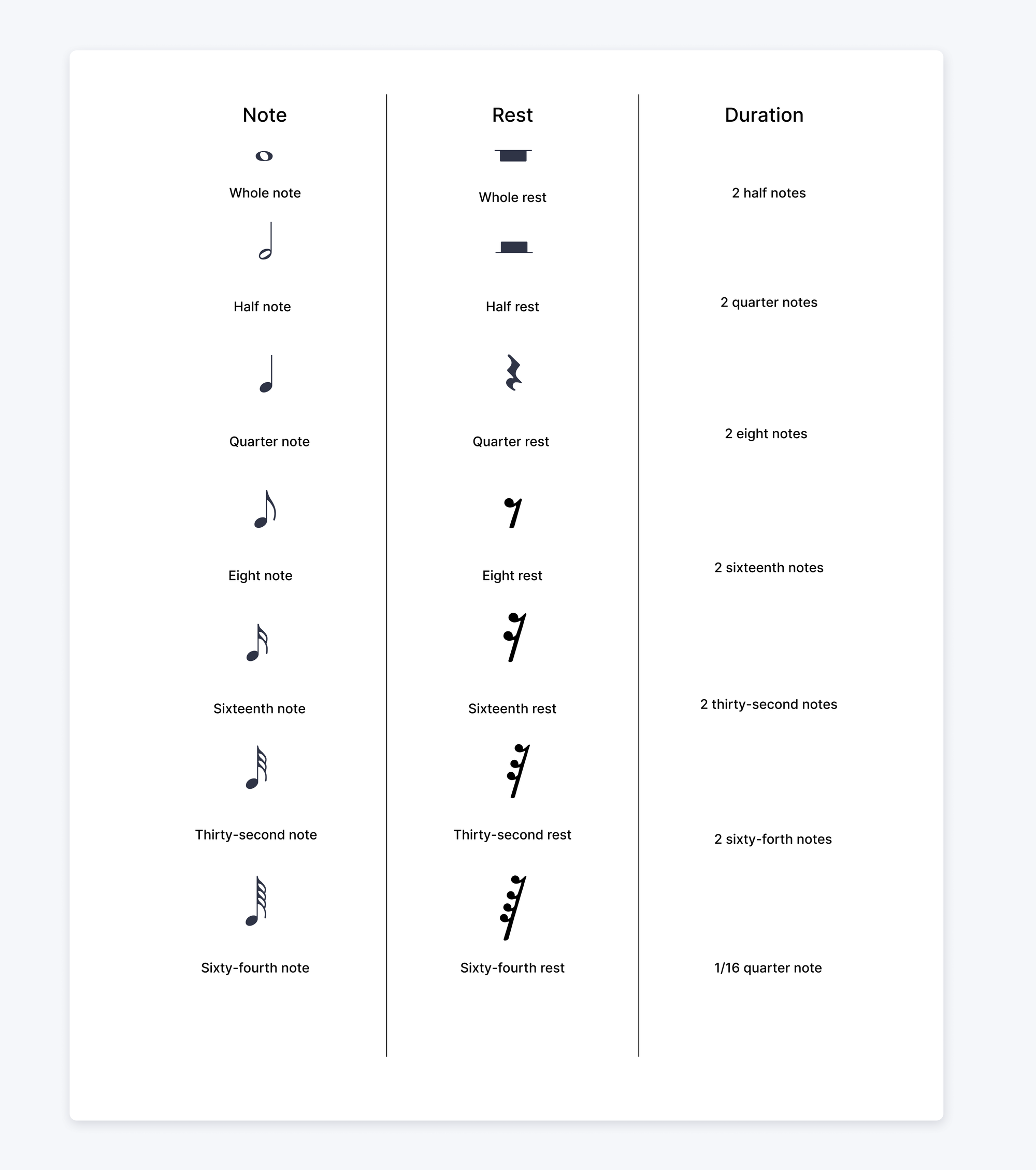

Types of Notes by Duration

The shape of a note shows how long it lasts. Each note also has a matching rest symbol that represents silence for the same amount of time. Notes are organized by values, each one twice or half the length of another.

Dotted Notes

In music notation there is something called dots. A dot is placed immediately to the right of a note (or rest) and it changes its duration. The rule is simple: a dot adds half the value of the note it follows.

- A dotted half note lasts 3 beats in 4/4 time (2 + 1).

- A dotted quarter note lasts 1½ beats (1 + ½).

- A dotted eighth note lasts ¾ of a beat (½ + ¼).

Dots can also be applied to rests, making the silence last longer in the same way.

You may understand the concept more clearly by playing the score below. Notice how the note’s duration changes when a dot is added.

If you are not familiar with the concept of time signatures or beats, please check the guide below:

Double and triple dots

Although less common, notes can have two or even three dots:

- A double dot adds half the value of the first dot (e.g., a half note with two dots = 3½ beats).

- A triple dot adds half again (used rarely, usually in advanced scores).

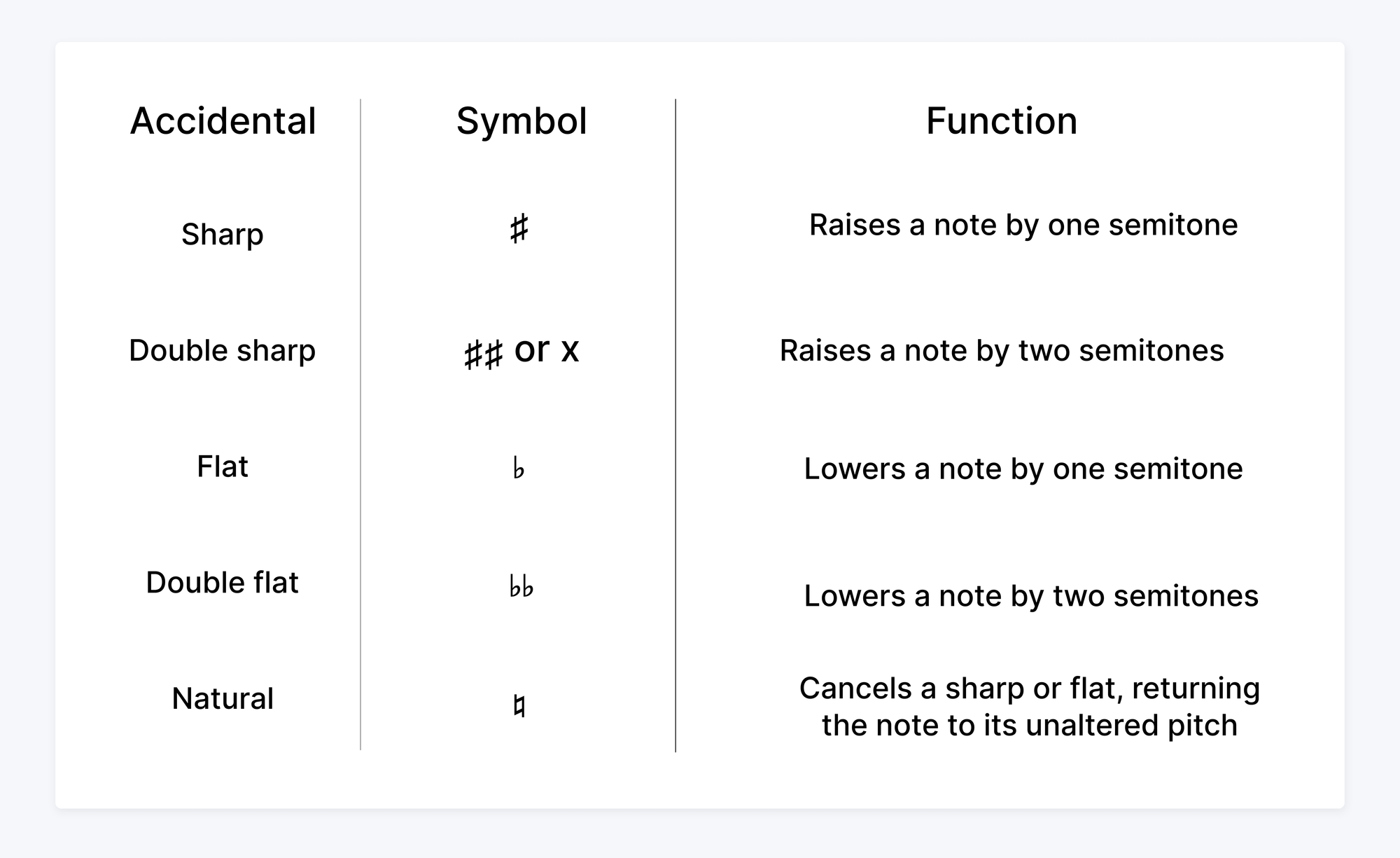

Accidentals and Pitch Changes

Accidentals are symbols that change the pitch of a note, either raising or lowering it by small steps. They expand the basic set of natural notes into the full set of 12 pitches used in Western music, which makes them essential for melody, harmony, and modulation.

If you’re not yet familiar with semitones, I suggest checking out this guide—it will help you master the concept:

Sometimes, two notes may look different on the page and have different names, but they sound the same. For example:

- C♯ and D♭

- B♯ and C

- E and F♭

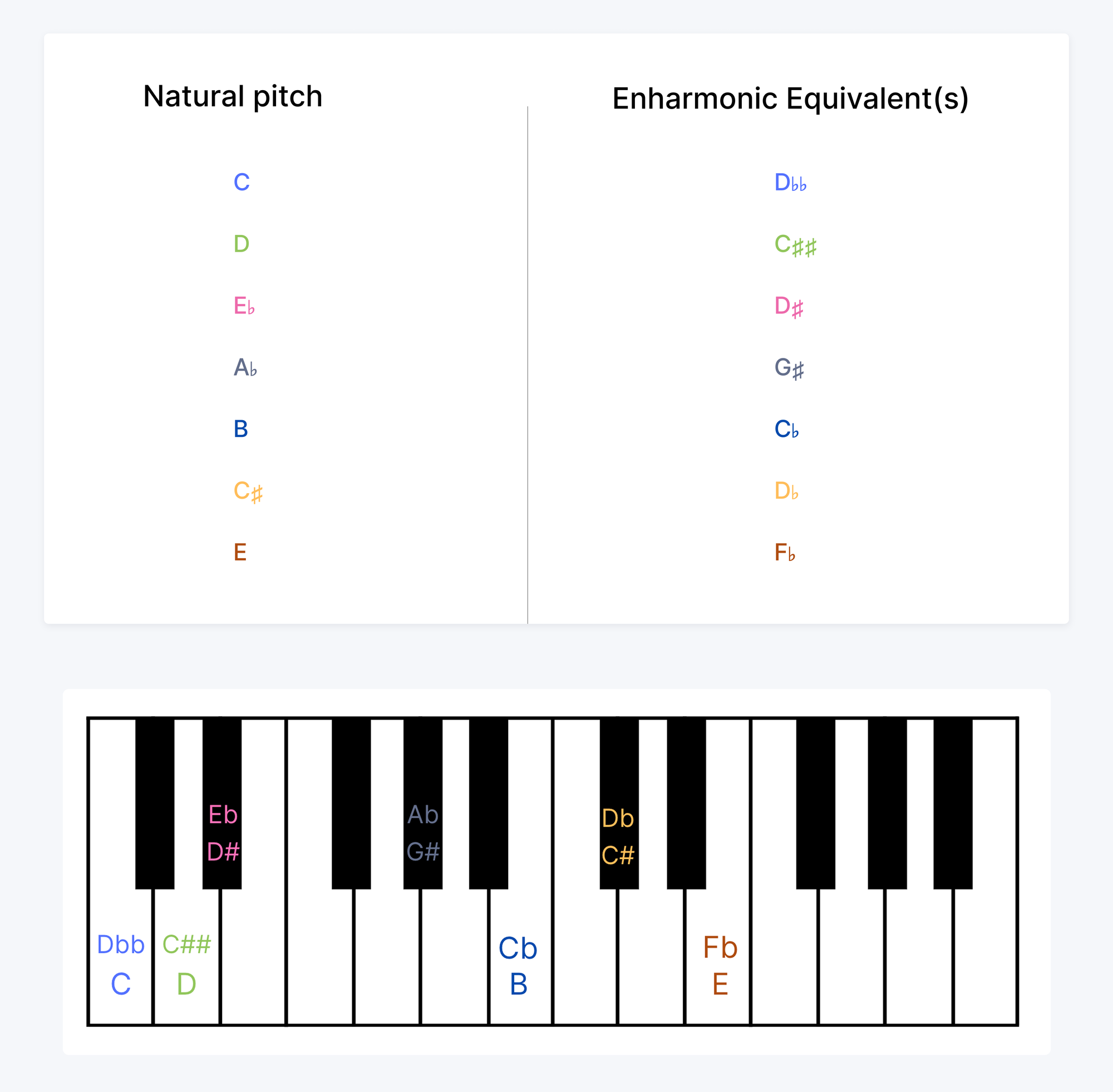

These are called enharmonic equivalents. To make this clearer, look at the diagram and the score below. In the diagram, you can see examples of enharmonic notes along with their positions on the keyboard.

In the score, you’ll notice they are written with different names but sound the same when played back.

💡 Accidentals are crucial because they give you access to every possible pitch. They let you add emotional color, create tension and release, and shape melodies in ways that simple natural notes can’t.

Tools to Help You Learn and Write Notes in Sheet Music

Getting comfortable with musical notes is much easier when you use the right tools. While pencil and paper still work, digital notation software can speed up the process, reduce mistakes, and help you actually listen what you’ve written.

One of the best options for beginners and experienced composers alike is Flat. With Flat, you can:

- Insert notes directly on the staff with a simple click or keyboard shortcuts.

- Hear playback instantly, so you know right away if the pitch or duration is correct.

- See rhythms clearly, since the software automatically aligns stems, beams, and rests.

- Avoid common errors, like misplacing accidentals or mixing up note values, because the program applies rules of notation automatically.

By using a tool like Flat, you don’t just learn faster—you also build confidence.

Notes are the heart of sheet music—the symbols that shape pitch, rhythm, and flow. Once you learn how to read their values, place them on the staff, and handle accidentals, you’re stepping into the universal language that musicians everywhere rely on. Like any language, fluency comes with practice.

So why wait? Start your next score by mastering the basics of notes today, and let playback guide you as you explore how pitch and rhythm work hand in hand.